Lost in Big Bend country

Our road trip started with a low tire pressure warning as the sun was setting along the Rio Grande. Ahead was 50 miles of curving road hugging the river from the border town of Presidio to Big Bend National Park in southwest Texas, conveniently located squarely between nowhere and nothing.

We had planned to make the drive in the early evening, when the sun was lower in the sky and the late-June temperatures dipped from 100 into the mid-80s, but three enchiladas and one bowl of very hot green chile salsa later, we found ourselves on the other side of dusk.

We’d already been given warnings about Big Bend, from hiking early to avoid the heat – but being sure to talk while walking so as not to surprise any snakes or bears – to drinking enough water to avoid deadly heat stroke and requiring a special ranger to pick up our bodies from the rocky trail, to staying away from the border all together to avoid armed ‘coyotes’ smuggling Mexicans across the treacherous territory. Yet we were still on our way, via El Paso and Marfa, Texas, to the least visited national park in the country. Just because. And nothing was going to stop us.

And now, on a road where we’d only seen an occasional border control vehicle, one of our tires was threatening to strand us. We doubled back and found a service station that had just switched off its ‘open’ sign and begged them to take a look. There was a screw firmly lodged in the back tire. As the attendant in his dark blue uniform pulled the tire off with a whir, stripped the rubber from the rim, and proceeded to plug the hole, he gave us more warnings about Big Bend.

This road we were taking was windy and hilly and dangerous and required our full attention. We should go the speed limit, he said. We might even get motion sickness. Did we have any Dramamine? And at this time of night the animals would be coming down from the mountains to water, so we should look out for javelinas (a pig-like animal about the size of a dog) and even mountain lions crossing the road.

Then he sent us on our merry way. After narrowly escaping an overnight spent on the edge of a canyon with a flat tire and marauding wildlife circling our car looking for snacks, we set off for our destination, an unlikely golf resort at the edge of the desert park.

The road was indeed hilly, the kind of hills you can’t see over once you get to the top and then dip down like a sliding board – the sign warned about a 15% grade– and we could sense that somewhere out there in the pitch blackness (there was no moon that night) was a great nothingness, a deep canyon, to the right, and soaring rock all around. Sure enough, a javelina scurried past the headlights of our car, a skunk waddled along the side of the road, and miniature kangaroo rats skitted across the road as if on tiny rollerskates. It took forever to navigate the twists and turns, and when we finally settled into our beds, it was midnight. We couldn’t wait to see what kind of country we would wake up in.

Big Bend National Park is big. Texas big. 800,000 acres. That’s slightly larger than Rhode Island. It’s the meeting of Texas and the states of Coahuila and Chihuahua in Mexico, separated only by high canyon walls and the twisting Rio Grande.

It is the Chihuahuan desert, Chisos mountains, and the river converging in one place. It is 200 miles from the closest Wal Mart. Water and gasoline sources are few and far between, according to the park brochure. And cell phone service is limited and unreliable.

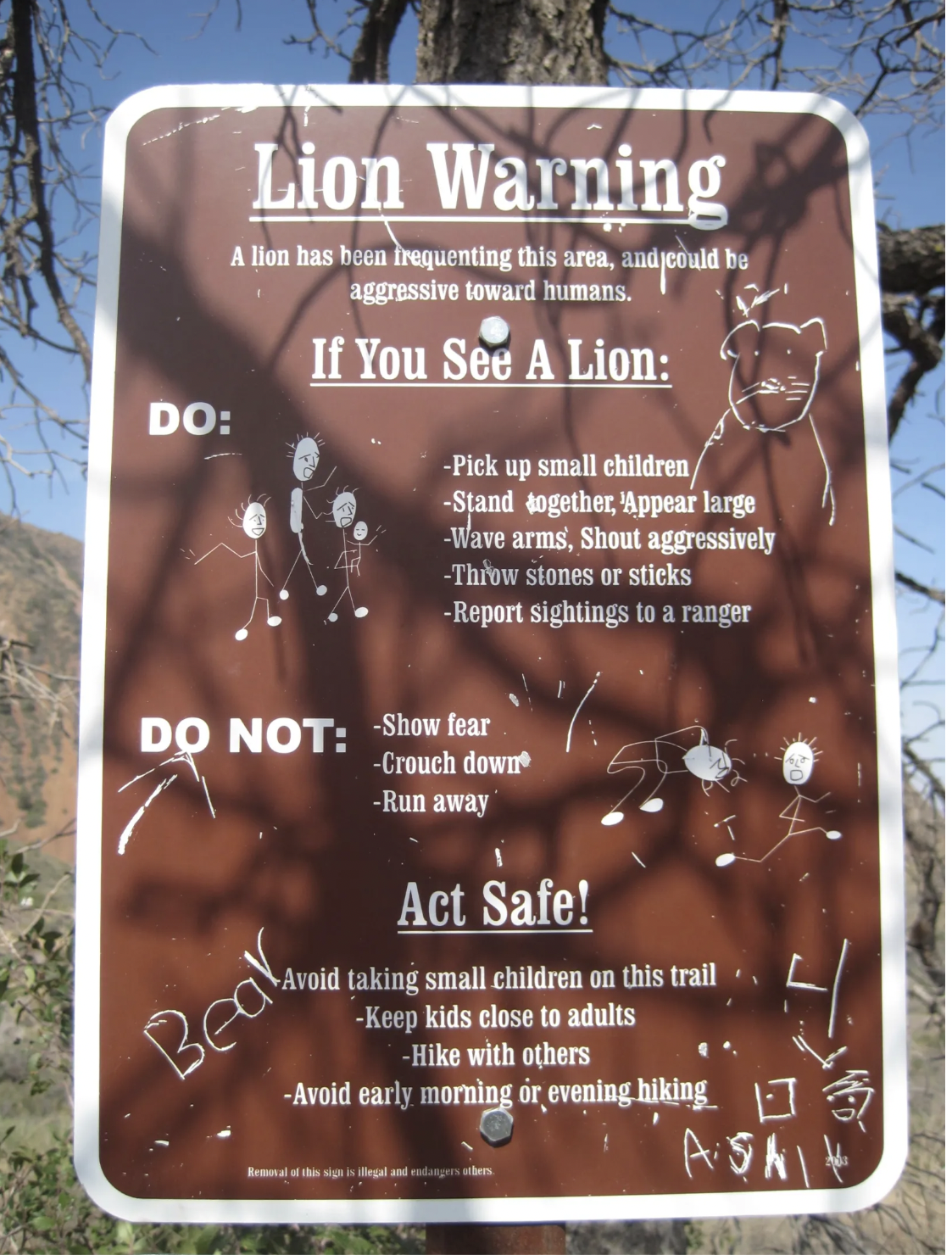

It’s also worth noting that half of the brochure is written in red type and outlines the various dangers you may encounter while in the park, ranging from the lack of medical facilities (the nearest hospital is 100 miles away), the power of heat to kill (carry a gallon of water per person per day), how to not get swept away in your car during flash floods, being prepared for encounters with mountain lions and bears, keeping an eye out for four species of rattlesnake and one species of copperhead, and how washes can become raging rivers while you sleep so don’t camp in low spots. Oh, and you shouldn’t swim or wade in the Rio Grande because it has strong currents.

Obviously, we were excited about getting to the park. We woke early to hike before it got too hot. Temperatures had been hovering around 110 for the past week. We were told to hike in the coolest part of the park, the basin, to get the most out of our visit without suffering from heat exhaustion. Instead of staying right in the park, we chose a resort built around a fake western town and a golf course with a pool to cool us off during the afternoon hours. The Chisos Mountain Lodge, the only lodge in the park, offers immediate access to several trailheads, but it doesn’t have a pool.

Things are really big in Texas, so we traveled 30 miles to the entrance of the park, picking up some sausage and egg biscuits wrapped in aluminum foil at the only gas station/convenience store/café on the way. By the time we were in the park, the sun was warming the rattlesnakes I imagined basking near the trails. The ranger station was still closed, but there were helpful notices posted outside, including a picture of an angry looking mountain lion skulking through a field of wildflowers with news that the cats had been spotted at close range. Precautions should be taken: leave small children at home, do not run, wave your arms and throw rocks and do anything possible to aggressively defend yourself. There was a sample of the paw print to scale. I noted it was about 3 inches across. Inside the visitors center looked to be a stuffed mountain lion staring back out at me.

Equipped with lots of water, white long sleeve shirts, hats, and moistened bandana saround our necks to help keep us cool, we set off into the wilderness. We shared the hike with an ornithology class from the University of Texas, which was reassuring in terms of mountain lion protection since a group was ahead of us and a group was behind us. I was told by a local that best way to survive a mountain lion attack was to run faster than the other guy.

We didn’t see a mountain lion. (You don’t see them; they see you, I was also told.) But we did descend two miles from a rocky desert lined with prickly pair cactus and sparse trees and an occasional plus-size log of petrified wood into a dry, pebbly river bed in a high-walled canyon with sacred shade and a breeze that led us to a pour off, an opening in the canyon that let the river flow down 200 feet on the side like a waterfall. It was impossible to see over the side, the river having polished the stone to a dangerous sheen, but we were high enough to make my heart quicken just to take a peek.

On the way back, after shushing my traveling companion after hearing some snaps and crackles echoing off the rocks, we spotted a black bear with a pointy brown snout, an adolescent, canoolding on the hillside. We took a quick look and kept moving as the sun rose in the sky, ending our four-mile hike in a couple of hours – and at about 99 degrees by mid-morning.

We cooled off in the camp store and gathered supplies for the afternoon. Lunch meat, string cheese, corn tortillas, potato chips, and more water. We planned to take an air-conditioned cruise along the Ross Maxwell Science Drive through Santa Elena Canyon, one of the park’s best-known features. There are short trails along the route, but it was hot, so we were content to pull to the edge of the turnoffs to see Mule Ears, renowned rocky peaks with a natural spring at the bottom, and low hills that reveal the geologic history of the land as we descended into the canyon.

Some 40 miles later (remember things are big in Texas), we found the Terlingua Creek and the gateway to Mexico at the bottom of the canyon and the end of the paved road. The temperature was 108 degrees. I was incapable of exiting the vehicle at such temperatures, but my sturdy driver wanted to see the river up close. After an interminable ten minutes during which I exhausted every possible nightmare scenario in my mind about what might happen to her out there by herself, she returned covered in stinky gray mud up to her shins. She has gotten stuck in the so-called ‘sucky mud’ along the river, and had some trouble making it back in her flip-flops.

There is a trail here that leads through a narrow canyon to a grand overlook of the Rio Grande, but it was too hot and high time return to a safer place. Somewhere where we might run into other people and be cool and hydrated. Somewhere I didn’t fear dying in a stalled car at the bottom of a canyon. So we headed to the pool, where we dreamed about the roadside BBQ joint we saw on the way back from the park.

Maybe ten feet off the road on a patch of gravel at the edge of the desert was a small metal trailer and bamboo covered dining area with picnic tables and a menagerie of knickknacks, like a dancing toaster with sunglasses and a crab caught in a net. We pulled in just as the sun fell behind the Chisos Mountains and the desert breeze kicked in. Angel descended from the trailer stairs and informed us that she had four kinds of meat that night: brisket (smoked for 14 hours), pork bbq, beef ribs, and pulled pork.

“I haven’t mastered the pulled part quite yet,” she said, so we agreed that it would likely be more “chunked.” Our choice came with two sides: pinto beans so spicy and tasty that we drank the juice from the little white ceramic cup, and Arctic white potato salad with crunchy bits of celery and herbs.

It was a desert feast from heaven, and the smoked meat attracted a few locals. Stan, who had retired to an air-conditioned house on the yonder hill where he makes sun tea and sells Mexican pottery on his porch and helps out at the BBQ joint, and the man with the brown support socks, Bermuda shorts, and slicked back silver hair who arrived with a handful of stunning scenic desert photos that he had just taken in the morning and spent all afternoon printing. And the grizzled ghost of a man who seemed to appear out of the desert with a bandana and a backpack who was served a BBQ sandwich (and one to go) without actually ordering and responded to a friendly “How are you doing?” with a curt “Hot.” Dinner was followed by a styrofoam cup of complimentary peach cobbler that had gotten “too cold” to sell. It was delicious.

Morning brought new adventures. My heat resistant adventure partner joined a group with the Big Bend River Company to explore the river by canoe. Six of them (this is low season) took a leisurely half-day paddle complete with cheese snacks on the shore and an impromptu instruction on how to survive in the desert on plants like the pitayi cactus, which has edible strawberry-like fruit. I took an early morning trail ride with a genuine cowboy with a bushy white mutton chop moustache, fringed chaps, and gorgeously handmade green boots with silver spurs. He and his dog led me through a canyon where the Comanche Indians used to rob passing travelers from caves in the rocks.

I also checked out the Big Bend Ranch State Park Visitor Center and Warnock Education Center that includes an exhaustive introduction to the desert and its plants and rocks, as well as a replica of the 20-foot long wing of the 65 million-year-old pterosaur found in the park in 1971, the largest flying creature ever discovered. Big Bend is also dinosaur country.

Dinner this night took us to the Terlingua Ghost Town, the ruins of the Chisos Mining Company, home of an international chili cookoff, and the local hangout, the Starlight Theater. We passed the old cemetery with rocks piled on the graves of men who “succumbed to dangerous working conditions, gunfights, and the influenza epidemic of 1918” to find my traveling companion’s river guide hulahooping on the restaurant’s front porch. Two dogs were rolling the dirt mock fighting, and men with eyes wrinkled from squinting in the dry desert were leaning against the wall drinking cold beers.

The Venerable Clay Henry

The great-grand goat of the former mayor of Terlingua (yes, also a goat) died an untimely death by overindulging in his favorite pastime, drinking beer.

It was a busy night, the waitress said. Two-for-one burger night had brought in everyone within 50 miles, and we added tastings of the Big Bend Brewing Company beers and the best darn beef chili I’ve ever eaten. A duo played Neil Young songs in the corner (although it said that Robert Plant once dropped in to play a set), and a taxidermied goat with a beer bottle in its mouth, “the Venerable Clay Henry,” according the memorial plaque, watched over the festivities. He was the great grandson of the mayor of Terlingua (yes, the townspeople elected a goat to be mayor in the 1980s) who died an untimely death by overindulging in his favorite pastime, drinking beer.

The heat and the beer sent us off to early bedtime. And early the next morning, our visit ended on the very road on which we entered the park – River Road or FM-170–this time in dawn’s early light. As the mountains faded from purple to red, we saw what we didn’t see in the middle of the night on our perilous trip into Big Bend Country. On the right, sheer rock faces that reached into the blue sky and hugged the winding road that follow the ancient twists and turns of the river. On the left, a precipitous drop to low greenery and the water. Cattle freely crossed the border the graze. And on the other side, the mountains rising in Mexico, streaked with umber and black, hinting at miles and miles of rolling desert beyond. Besides a few road runners, we didn’t see a soul as we left this fierce territory. And despite all the warnings, we had survived.